A 12-year-old killed herself at a Spokane hospital that recently closed its youth psychiatric unit

InvestigateWest by Whitney Bryen and Kaylee Tornay, April 23, 2025. Workers say girl’s death is an example of what they feared from Providence closing the unit.

A12-year-old girl died by suicide this month after workers say she was left unsupervised at Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center, where she was waiting for a long-term psychiatric placement.

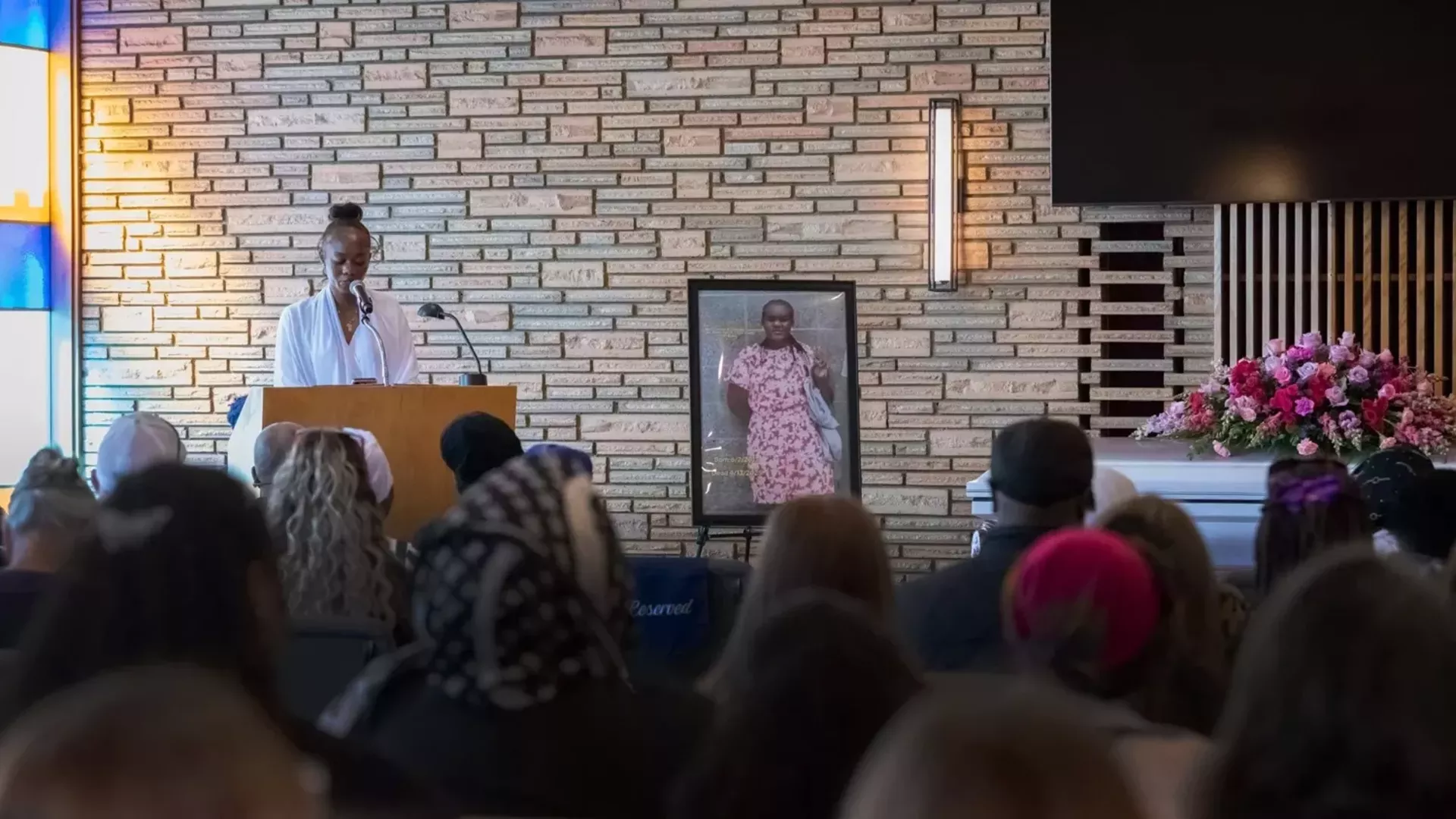

Sarah June Niyimbona, who had been receiving intermittent psychiatric care for self-harm and suicide attempts at the hospital over the last eight months, slipped out of her room without triggering the alarm and left the pediatric floor alone around 5:30 p.m. on April 13, according to a family member and three employees involved in her care. She then walked a quarter mile to the fourth floor of a parking structure on the hospital campus and jumped, dying two hours later in the emergency room.

“We’re confused how this could happen,” Sarah’s sister Asha Joseph said. “We also want to know why there wasn’t anyone there at the moment, why there was nobody watching her and how she was able to leave. We don’t really know anything. We don’t have any of the answers.”

Spokane’s Providence Sacred Heart has not released any information about Sarah’s death to the public. In response to InvestigateWest’s request for an interview, Providence spokeswoman Beth Hegde sent a statement by email: “We extend our sympathy to the family and loved ones affected by this tragic situation.” Providence refused to provide any additional information, citing privacy laws.

Sarah’s death, pieced together through interviews with health care providers and family, 911 calls, and a hospital report submitted to the state’s health department, comes just six months after the hospital closed its Psychiatric Center for Children and Adolescents. That decision was made over the objections of staff and community members concerned about a lack of beds for youth in need of inpatient mental health care. In February 2024, hospital executives wrote in a state grant application that the center, despite losing $2 million a year, provided lifesaving care to children and teens, and that nearby facilities would struggle to fill the gap if it closed. After closing the center, however, Sacred Heart CEO Susan Stacey minimized the impact, saying a for-profit facility in Spokane was ready to meet the demand.

Now, critics of the closure said Sarah’s death is an example of the harm they feared would come from the decision.

“When Sacred Heart closed its adolescent psychiatric unit just months ago, nurses, physicians, community members, and former patients and their families warned about the impact this would have on services for this highly vulnerable population,” said David Keepnews, executive director of the Washington State Nurses Association. “WSNA expressed concern about a decision that was based on the financial bottom line at the expense of the community’s needs.”

“We said this is what was going to happen,” said Kaili Timperley, a former nurse in the children’s psychiatric unit. “We said their plan was not an adequate plan. You can’t just put these kids in a medical room and expect everything to be OK. It’s why we tried to fight against it and get the word out.”

Youth who have threatened or attempted self-harm continue to languish in Sacred Heart’s emergency department and in the general pediatrics floor, where the hospital converted two rooms into new psychiatric beds last fall.

Read more from InvestigateWest.