From Our Newsroom Partners

Click the + sign on the right to filter stories by state.

- All

- Arizona

- California

- Colorado

- Georgia

- Illinois

- Montana

- new mexico

- Oklahoma

- Pennsylvania

- Tennessee

- Texas

- US

- Washington

- West Virginia

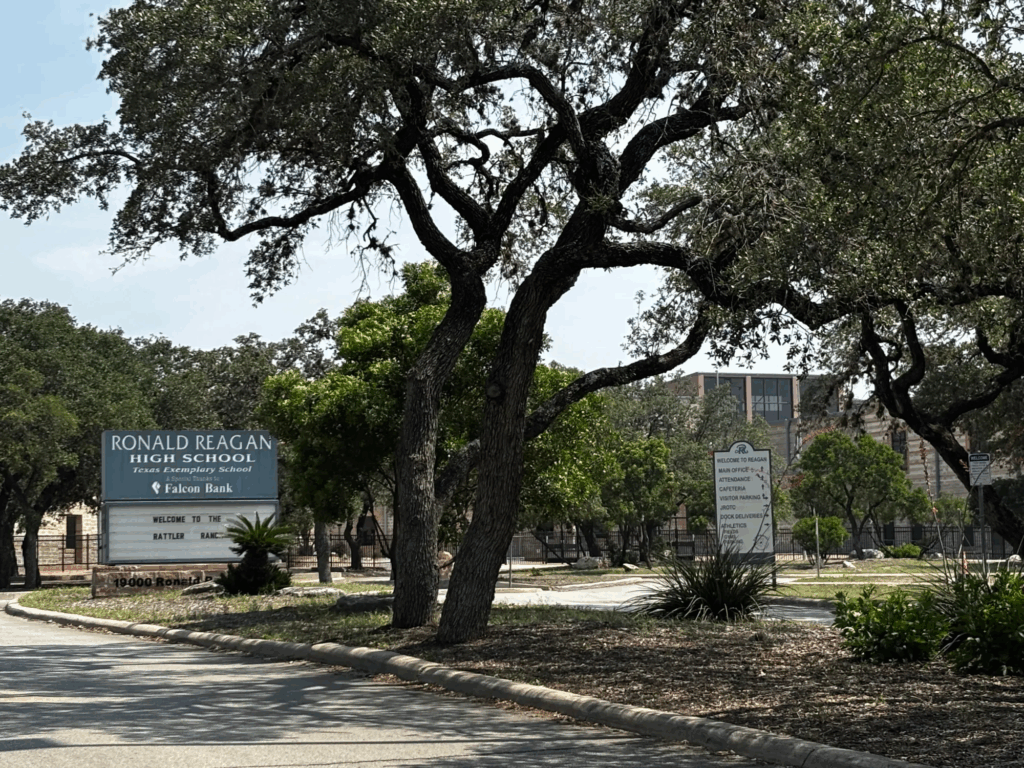

Texas Schools Fall Short on Resources to Address Student Mental Health Issues Before They Become Crises

From Public Health Watch

It was February of 2020, and Andy Gonzalez, then a junior at Reagan High School in San Antonio, was on his lunch break when he noticed a burst of activity among the faculty. Then the news began to spread.

WA health department investigating Spokane hospital after girl’s suicide sparked public outcry

From InvestigateWest

The Washington Department of Health is investigating a 12-year-old’s suicide at Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center last month that has prompted heartbreak and outrage from lawmakers, Spokane city councilmembers and behavioral health advocates statewide.

Religious Contacts, Student Volunteers Find Themselves in Midst of Mental Health Crisis

From Grady Newsource

Rylie Hamilton meets on Tuesday evenings with three female University of Georgia students to discuss a range of topics, from spirituality to navigating the dating sphere to test anxiety. Mental health is frequently part of the conversation.

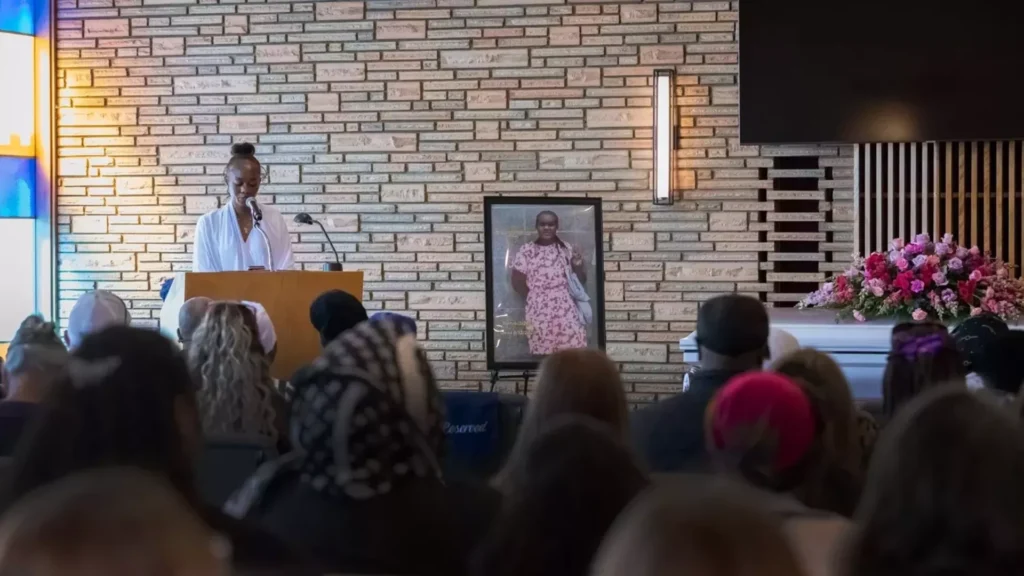

A 12-year-old killed herself at a Spokane hospital that recently closed its youth psychiatric unit

From InvestigateWest

A12-year-old girl died by suicide this month after workers say she was left unsupervised at Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center, where she was waiting for a long-term psychiatric placement.

Language lives on for tribes in Oklahoma despite determined erasure attempts

From KOSU

More than a century after U.S. Indian boarding schools attempted to erase Indigenous cultures and languages, tribal nations in Oklahoma are working to reclaim and teach their languages to the youth. Despite research showing how language learning can improve mental health outcomes, world language credits are not required for graduation following recent state legislation.

Mental health advocates fight stigma to curb conditions that can kill new moms in Georgia

From WABE

A couple of years ago after having her second baby, Jana Kogon barely slept.

The Atlanta mom’s mind kept racing with thoughts of all the bad things that could happen. Her fears all revolved around her children, she said.

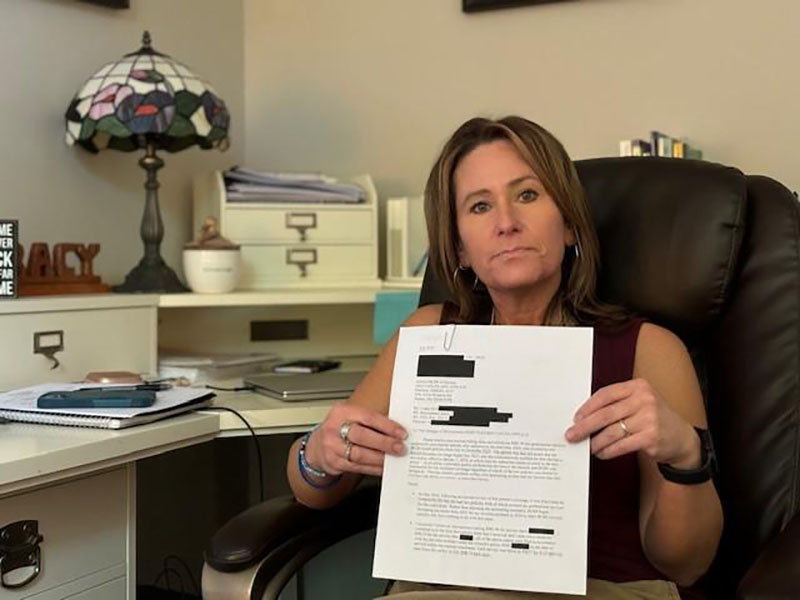

So-called insurance ‘clawbacks’ are driving Georgia mental health therapists into private practice

From Georgia Public Broadcasting

Many therapists want to be accessible to clients with insurance, but doing so is risky when billing errors and complex coding rules lead insurance companies to “claw back” previously paid reimbursements.

Soaring housing costs make life even more challenging for Oakland’s unaccompanied minors

From El Tímpano

Jorge arrived in the United States aged 16 and roughly $9,000 in debt to those who helped him make the harrowing journey from Guatemala to California.

The day after he arrived in Oakland, he found a job cleaning roofs and attics and eventually working in construction.

OVERWHELMED: Autistic patients say conditions at Arizona State Hospital are making them worse

From KJZZZ

Matt Solan is overwhelmed.

Solan has been a patient at the Arizona State Hospital since April 2020, found guilty of aggravated assault with a deadly weapon. Because he was found to be “guilty but insane,” a special designation in Arizona law, Solan was sent to ASH, as it’s often known, instead of prison.