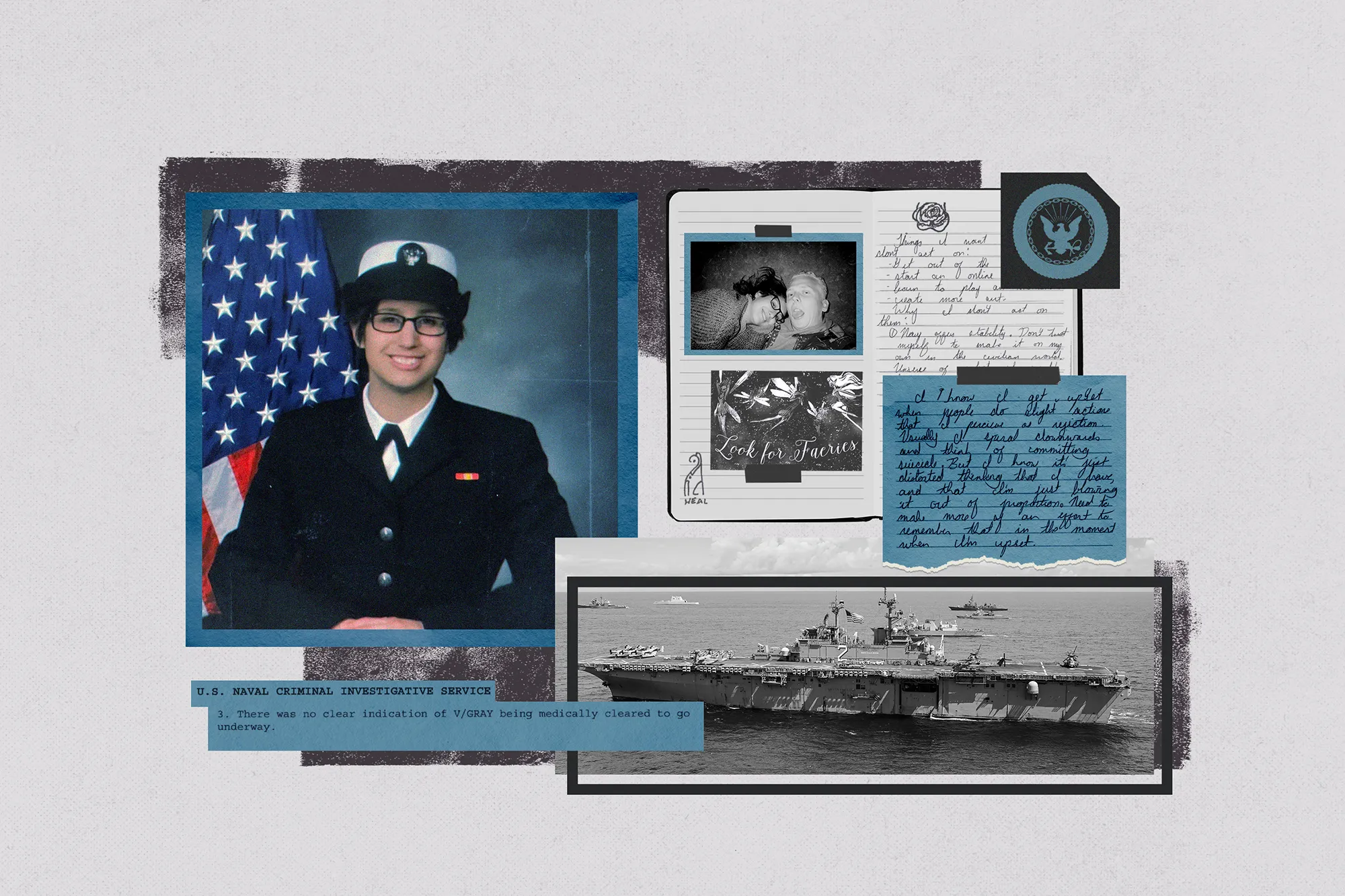

Deadly Failure: A Sailor Was in Crisis. Her Command Kept the Pressure on Anyway

Voice of San Diego by Will Huntsberry, April 2, 2024: March 6, 2018, was another mild and sunny day in San Diego. Petty Officer 2nd Class Tiara Gray, who was 21 years old, was somewhere off the coast, onboard the USS Essex, writing in her journal. It was 27 days before she died.

I sat on the hangar bay today. I felt the sun warm my skin and the shadows move as we rocked slowly back and forth.

I haven’t been feeling like writing lately and I fear it’s because I don’t want to reflect inward.

I want to be strong and powerful. I want to be sure of myself. I want to have a deep understanding of myself.

I know I get upset when people do slight actions that I perceive as rejection. Usually, I spiral downwards and think of committing suicide. But I know it’s just distorted thinking that I have and that I’m just blowing it out of proportion. Need to make more of an effort to remember that in the moment when I’m upset.

**

Tiara’s journal is full of ghostly footprints. She spends a lot of time at Lestat’s in Normal Heights writing and people watching. She goes to see a local punk band, The Frights, at SOMA, one of the only under-21 venues in San Diego. (The lead singer gets drunk and can barely finish the show.) She goes to a house party in North County. (People dance on the roof. “I wish I were as free as [them,]” she writes.) She hangs out by the pool. She goes to Joshua Tree. “I have a feeling no amount of time out here could satisfy me,” she writes.

She experiments with tarot cards and crystals, but she’s not so sure. “I’m not 100 percent sold on the magical concepts in this book, but I have my own ideas,” she writes. “Ritual and prayer solidify your intent to achieve something.”

She feels as if she doesn’t see herself clearly. But some days her vision of herself comes into focus.

“Why am I basing my actions on other people’s opinions?” she asks. “When we make decisions based on insecurity, we lose our individuality and instead become a representation of other people’s expectations.”

Other days she judges herself without compassion. She writes of her childhood:

“I wasn’t abused. It was my fault for being disrespectful and rude. Nothing made me happy. I was ungrateful, awful to be around … And I’m still just that stupid, ungrateful, annoying, horrid girl. I haven’t gotten any better. I don’t know how people stand to be around me.”

This story draws on thousands of pages of documents — from medical records and a death investigation to interviews of Tiara’s shipmates and a lawsuit. It draws on multiple hours-long conversations with the people who knew her best. And it draws on the words she left behind.

Her journal tells the story of a person coming of age, trying to know her place in the world.

Her Navy records tell a different story. Navy doctors note that she has severe anxiety and diagnose her with major depressive disorder. They acknowledge that her high-pressure job exacerbates her conditions. They hospitalize her twice and put her in a 35-day inpatient treatment program. More than 25 different Navy mental health providers treat her. They give her conflicting evaluations and recommendations. Some mark her fit for duty. Others do not.

Eventually, they send her back into the demanding environment that set her off. Together, the thousands of pages of documents and hours of interviews say one thing clearly: The treatment Tiara received in the Navy played a role in her death.

Read more from Voice of San Diego here.