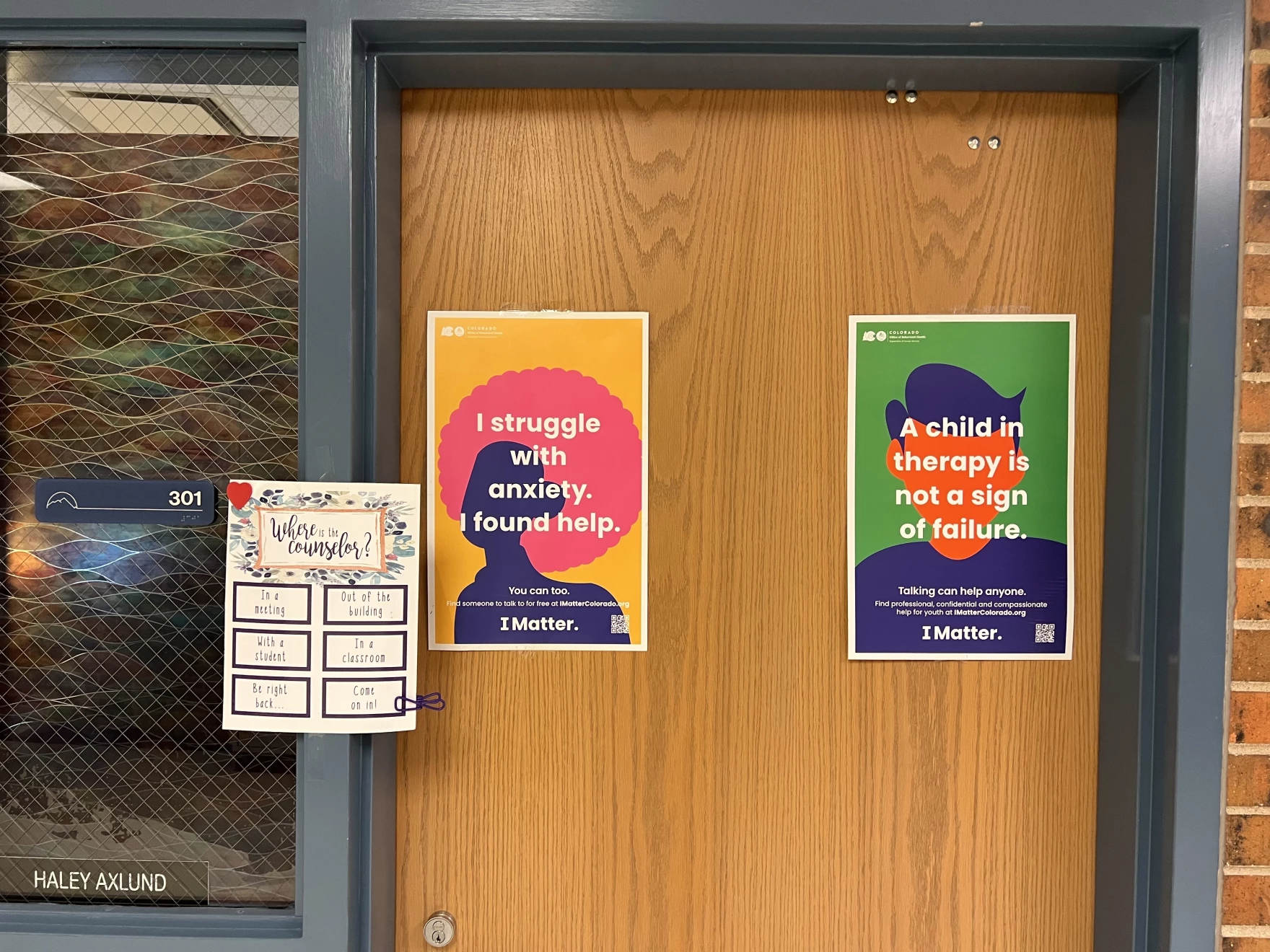

From long wait lists to high costs, finding a therapist in Colorado is harder than it should be

KUNC by Leigh Paterson, November 15, 2023: In communities across Northern Colorado, people are struggling with their mental health while also struggling to get the care they need.

The problem is widespread. Around a quarter of residents reported having poor mental health in the most recent Colorado Health Access Survey. Out of the 1 in 6 Coloradans who were unable to get needed care, nearly half said they had a hard time getting an appointment, while nearly 60% were concerned about cost.

Fort Collins resident Kristin Vera has lived these statistics while trying to get her teenage daughter help over the past several years.

“Her mood was so extraordinarily low. And of course, I was worried about self-harm, suicide and also, it’s just hard to see your kid being miserable,” Vera told KUNC earlier this year.

During the pandemic, Vera had trouble finding a therapist who accepted insurance, had openings, and who would be a good fit for her daughter who was depressed and questioning her gender identity.

“I just remember the anxiety of being in that space of feeling like someone has got to help us. But who? Where are they?” Vera said.

Over the past few months, we have been reporting on the barriers residents face in getting help, despite laws in place to ensure insurance coverage. Here’s what you need to know about mental health parity laws.

What is mental health parity?

Federal and state parity laws require insurance companies to cover behavioral health services such as therapy in the same way that they cover physical health services such as doctor’s appointments. Parity laws prohibit insurance carriers from being more restrictive based on measures like copays and the number of covered appointments.

With some exceptions, mental health services are a covered benefit for most Coloradans with insurance. Still, residents regularly have trouble getting care.

“It can be really, honestly be like climbing Everest twice without oxygen to go from the moment of realizing that you need help and then within seven calendar days walking in or signing on to your first therapy session using your insurance,” said Cara Cheevers, the head of behavioral health at Colorado’s Division of Insurance, in reference to getting care within a week, as required by regulation.

Read more from KUNC here.