High need, low accessibility: Oglethorpe County residents face barriers to mental health care, even as teens and schools are willing to have the conversation

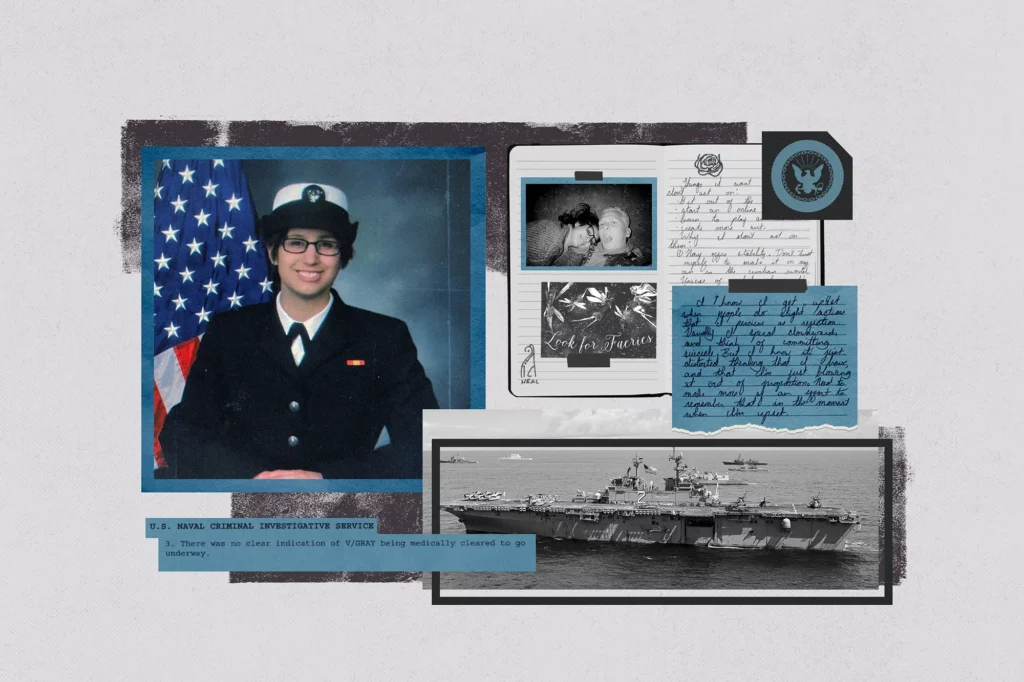

The Oglethorpe Echo/the Cox Institute’s Journalism Writing Lab at the University of Georgia by Navya Shukla and Sydney Rainwater, March 21, 2024: Sonja Thompson Roach remembers the moment last year when a photographer took photos and interviewed her son and his friends for a Time magazine story on mental health and teens.

The photo and interview shoot in her Northeast Georgia home required absolute quiet for the audio and the right time of day for the lighting.

But one thing stood out the most.

She heard her son, August, answer questions about his father’s death from COVID-19 in 2021, giving information to the photographer that would be helpful for other kids.

And Thompson Roach then heard his friends share their experiences being bullied.

She was proud of them for speaking out.

“It’s just so, so revealing, and you want to honor the fact that they’re really trying to deal with all of these things,” said Thompson Roach, who lived in Oglethorpe County and now lives in Hartwell. “And at the same time, really be attuned to maybe the fact that they are struggling with feelings that you really never even scratched the surface of as a parent.

Statistics indicate alarming rates of depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation among children and teens across Georgia and the U.S. Georgia ranks in the top 10 of states with youth with substance abuse disorder (No. 2) and those who experience major depression (No. 10), according to “The State of Mental Health America,” a 2023 report by Mental Health America, a national advocacy organization dedicated to mental health.

Care is particularly hard to come by in rural communities like Oglethorpe County that struggle to provide adequate mental health resources for children and families.

“In rural areas, there are very few providers, and the ones that are, are so restrained,” said Stacie Johnson, who worked in the mental health field for nine years as a counselor before becoming an advocacy coordinator for the Northeast Georgia Court Appointed Special Advocates.

With 15,469 residents spread over 442 square miles, Oglethorpe County — like other rural communities — struggles to attract health care providers. They are reluctant to set up practice in an area where families must travel long distances to access their services, which they may not be able to afford.

An estimated 12.7% of Oglethorpe County residents live in poverty, according to 2022 U.S. Census data, compared to the national rate of 11.5%.

Due to shortages of mental health care workers and limited health care coverage, the rate of uninsured individuals in Oglethorpe County under the age of 65 is double the national average, according to Census data. Many families rely on schools to fill the gaps.

Read more from The Oglethorpe Echo/the Cox Institute’s Journalism Writing Lab at the University of Georgia here.