People with mental illness are more likely to die in jail. A new Oklahoma County program puts them in treatment instead

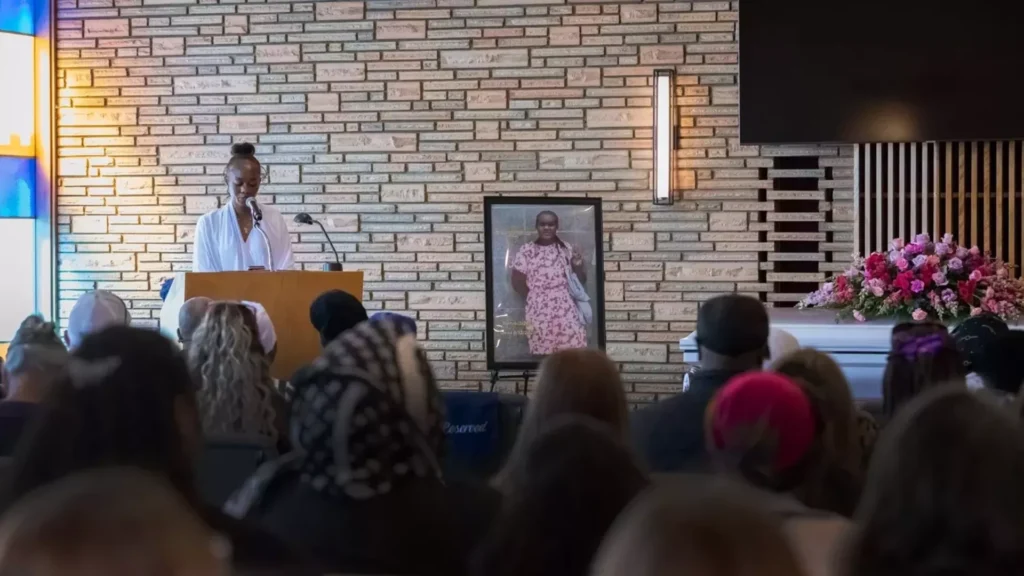

The Frontier, by Kayla Branch, August 31, 2023: There have been nine suicides at the Oklahoma County jail in three years. Another six people with documented mental health issues died of other causes. One woman’s death has helped jumpstart a diversion program.

After her arrest for a small amount of methamphetamine in 2017, U.S. Army veteran Krysten Gonzalez signed an Oklahoma County Mental Health Court contract agreeing to behavioral health treatment in exchange for the chance to stay out of prison.

The requirements were extensive: She promised to make every court hearing, treatment appointment, support group and probation check-in. She couldn’t use drugs or alcohol and would undergo regular drug testing. She could be searched at any time. She was required to pay $960 in probation fees. And she couldn’t associate with anyone who had a felony conviction.

Gonzalez was sexually assaulted during her time in the Army and endured years of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and struggles with substance use, said Derek Franseen, an attorney for Gonzalez’ family who is suing the county on her behalf. The court listed Gonzalez as homeless. Between 2016 and 2018, she was charged with possession three times, obstructing an officer and breaking and entering a stranger’s house in Midwest City to ask if she could use the bathroom.

The mental health court agreement was difficult for her to manage. Without permanent housing, transportation or a cell phone, court officials say the requirements can be challenging for people with serious mental illness. If they miss appointments or don’t maintain sobriety, they can fail the program and end up in prison.

A judge issued warrants for her arrest when Gonzalez missed court dates. She was booked into the Oklahoma County Detention Center in October 2018 and held without bond while the county searched for a bed at an inpatient mental health treatment facility. She was still waiting in January 2019 when she died by suicide alone in her cell at age 29.

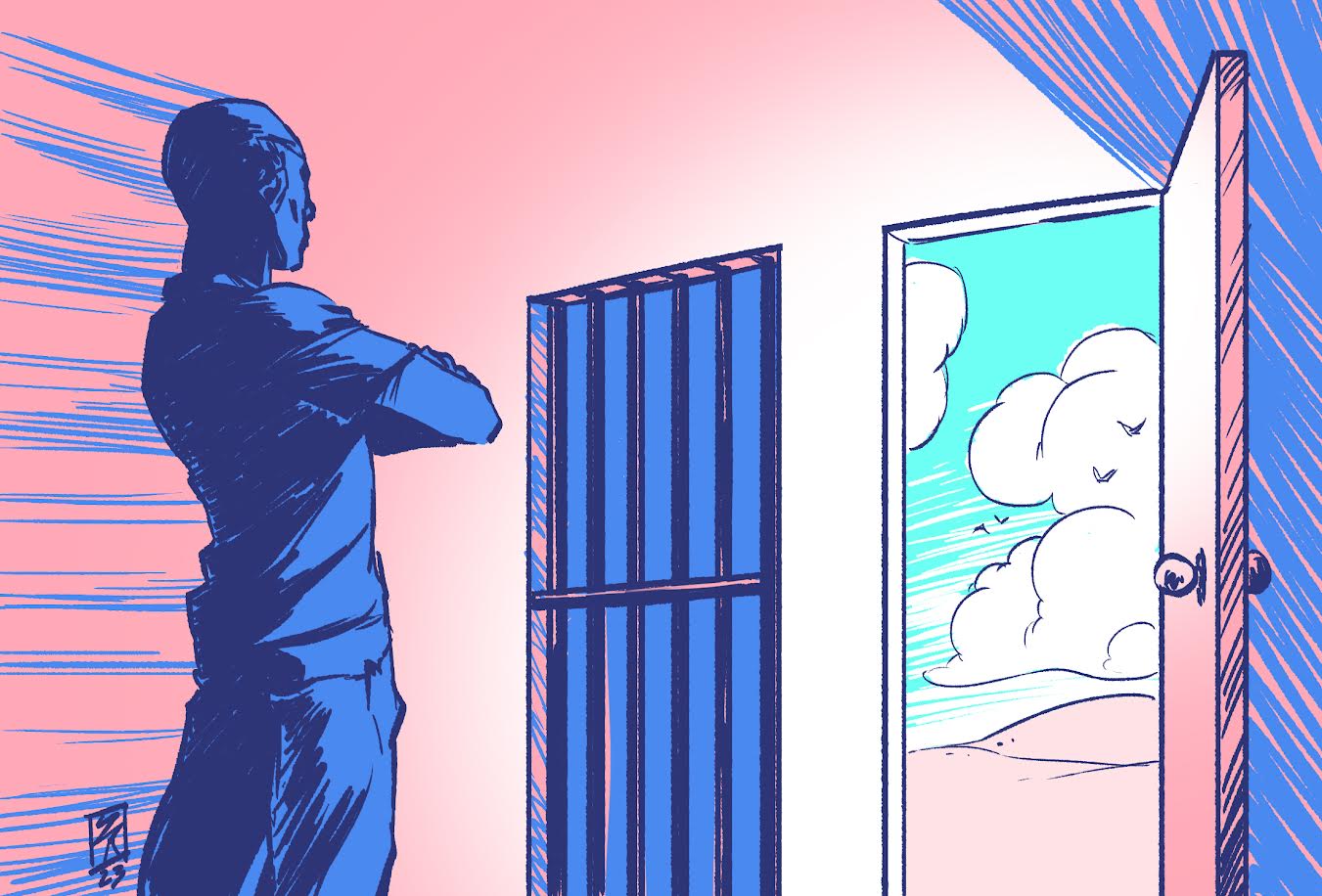

Illustration by Zach Raw/For The Frontier and Curbside Chronicle

Oklahoma County officials launched a new program this spring to pull people with mental health conditions and eligible offenses out of the jail entirely and send them to community-based treatment. The goal is to divert people from jail entirely, but the program has no funding yet.

The Court-Ordered Outpatient Treatment Program — CO-OP for short — has less supervision for participants than mental health court. Participants don’t have to come back to court every week, and their criminal charges are typically dropped up front. When a person isn’t complying with program requirements, law enforcement takes them to a treatment provider for a new assessment instead of back to jail.

“(Gonzalez is) the type of individual who probably would have been approved,” said Oklahoma County Public Defender Bob Ravitz. “She probably would have gotten out of jail and been alive, in my opinion.”

Read more from The Frontier here.