The Often Vicious Cycle Through SF’s Strained Mental Health Care and Detention System

San Francisco Public Press by Madison Alvarado and Yesica Prado, May 6, 2024: Dispatchers received at least 24,000 calls about mental health crises last year. Often, responders couldn’t find the people in distress.

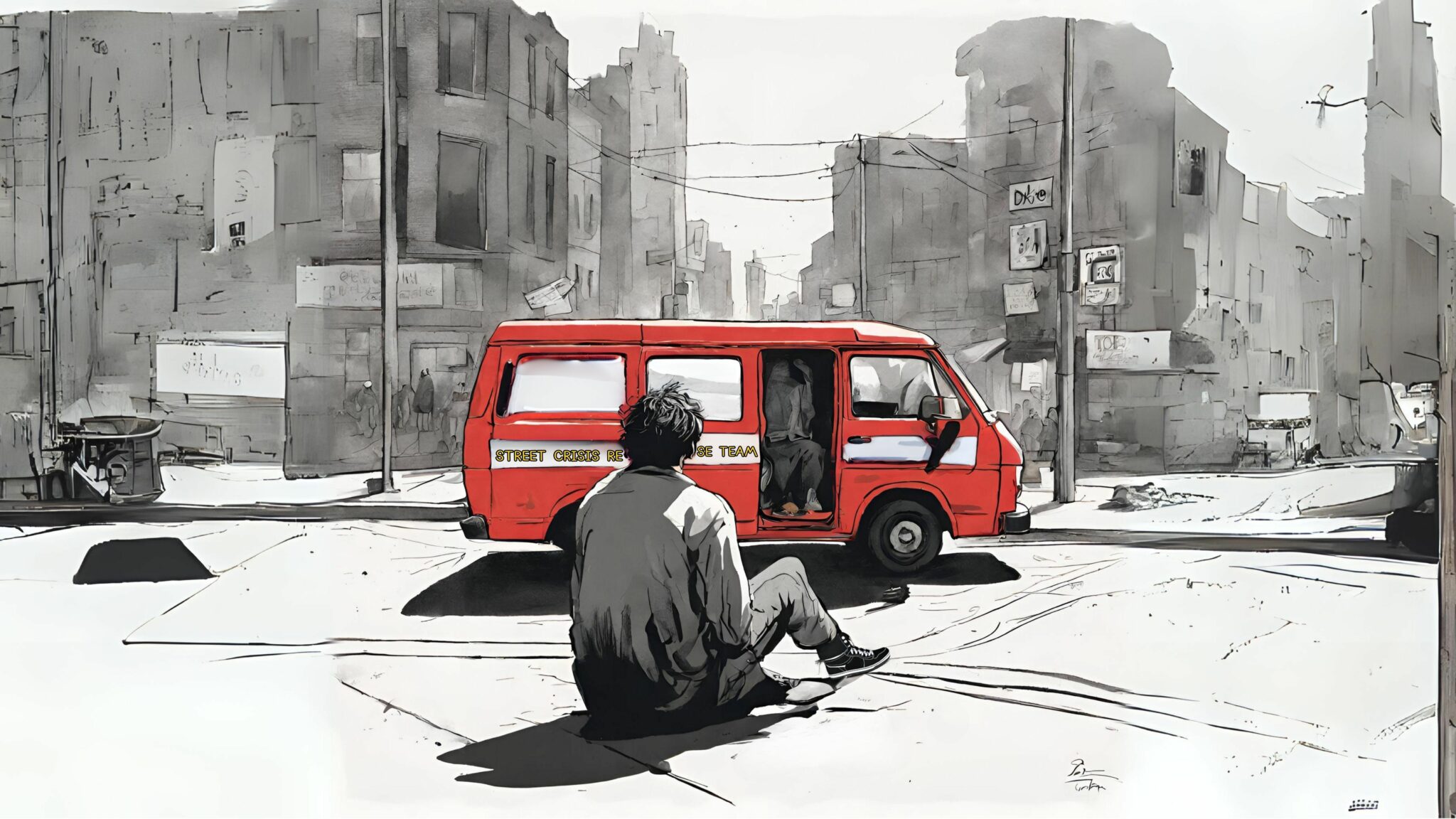

On a windy day last fall, a slender man stood on a corner of the bustling intersection at Van Ness Avenue and Market Street, anxiously seeking help. He flagged us down, asking that we call an ambulance. He said the dead leaves on the ground were out to hurt him and that his legs were bleeding. We didn’t see any blood. He told us his name was Jay and that he was unhoused.

Uncertain what to do, we dialed 311, San Francisco’s non-emergency helpline. Seventeen minutes later, a red van arrived, carrying members of the city’s Street Crisis Response Team. Jay told them he was schizophrenic. The paramedic recognized him from previous calls and greeted him. Looking at Jay’s digital records, a member of the group realized his prescription had been refilled about two weeks prior, but Jay didn’t remember picking it up.

As they spoke, it became clear that Jay had previously been placed under involuntary psychiatric detention, also called a “5150 hold.”

That fall day, Jay asked to be detained again.

That was how he had gotten a dose of Benadryl, one of two medications he used to manage his condition, he said. Benadryl is among the antihistamines that can help control anxiety. Schizophrenia requires lifelong treatment, even when symptoms have subsided.

“They give me my pill with a 5150,” he said.

The paramedic bristled. “That’s a lot of resources just to get one pill.”

Jay was one of thousands of people last year who fell into San Francisco’s complex, reactive, strained system for treating severe mental health and drug-related crises. As with many of the people who enter that system — including those who are unhoused or are detained without their consent following a call from an alarmed observer — Jay had received temporary care, entailing multiple involuntary psychiatric holds, that failed to address his long-term problems. That left him back on the streets to fend for himself or, with the help of passersby, try again to get the help he needed.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, much of the public discussion about homelessness and mental health in San Francisco has focused on the people who desperately need care, but who reject it. Jay’s story diverges from this common narrative.

“When’s the last time you were at Gen?” the paramedic asked, referring to the emergency room at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center, the facility in the city with the highest number of beds for people on 5150 holds.

“Today,” Jay said. He had gone there seeking medication, then waited in a hallway for four hours before staff gave him a dose of Risperdal, an antipsychotic that he did not usually take. It had not been effective.

Read more from San Francisco Public Press here.