This Harris County program serves the most vulnerable. But it won’t bail them out of jail.

Houston Landing, by Alex Stuckey and Marie D. De Jesús: This story is the third in a broader series, “Deadly Detention,” investigating jails across Texas. You can read the first story here and the second here.

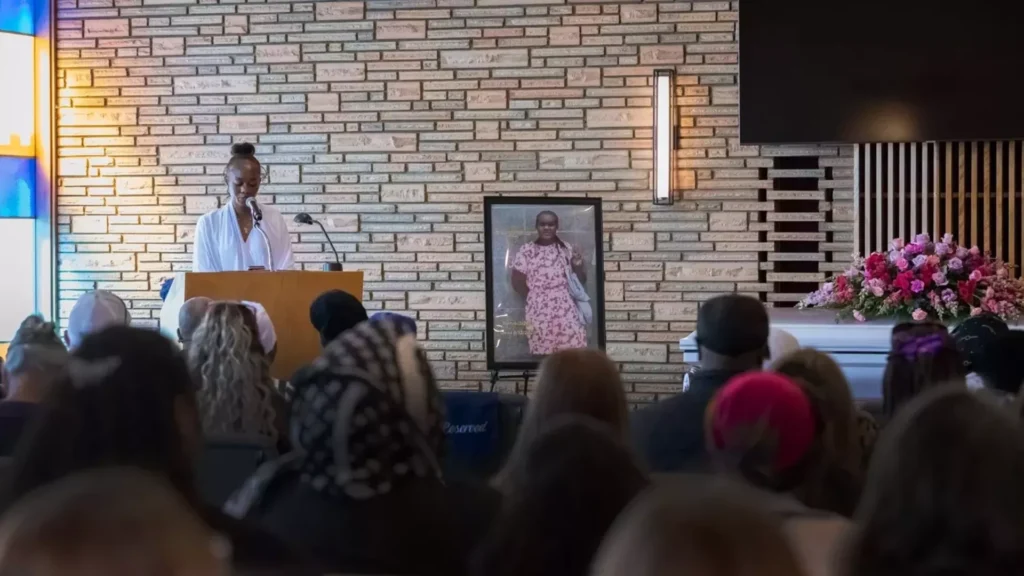

When a Houston police officer arrived at Richelle Morris’ group home in a quiet Greater Greenspoint cul-de-sac in October, she demanded to be taken to a mental hospital – or jail.

It was the day before Halloween, and Richelle, a 49-year-old with severe mental illness, initially called the police about a fellow resident at the home. But now, she wanted to be taken away.

The officer refused. Richelle, who was found mentally incapacitated in 2003, attempted to fight the officer. He grabbed both of her arms. She kicked him.

Inflatable ghouls and pumpkins stood sentry at a house across the street as Richelle was handcuffed and taken to jail, charged with felonious assault on a peace officer.

All she needed was around $500 and a promise to appear at her next court date to get out.

But the Harris County Guardianship Program – which oversees the affairs of Richelle and 1,100 other county residents with mental illnesses, developmental disabilities, mental deterioration or physical incapacities – did not post bond.

The county’s inaction would have catastrophic consequences for her.

Law enforcement officials and advocates for years have said that people with mental health concerns do not belong in jail – that they should be diverted to treatment or receive care before they reach a crisis point and begin interacting with law enforcement.

The Harris County Jail has continued to struggle with caring for an influx of inmates with mental illnesses. A Houston Landing investigation, “Deadly Detention,” found that nearly 60 percent of the 62 people who died of unnatural causes in the custody of the Harris County Jail between 2012 and 2022 had been identified as mentally ill. Yet many of the inmates hadn’t received desperately needed care.

Richelle’s case shows that not even a county-funded program designed to help the most severely mentally ill can keep them out of jail.

Read more from Houston Landing here.