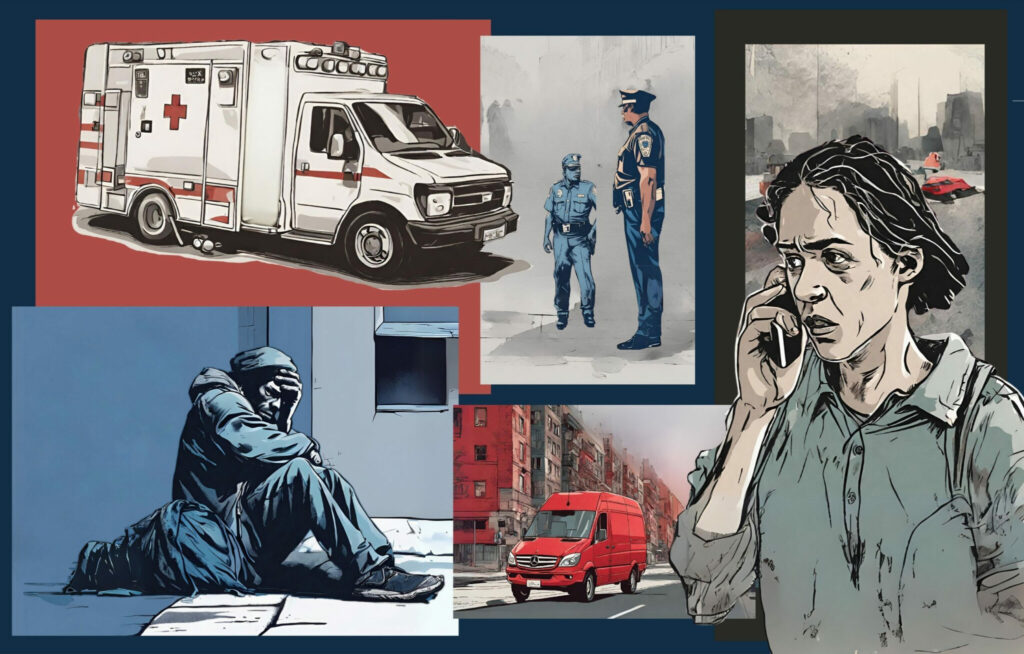

Law enforcement enlists mental health experts to help save lives — ‘a paradigm shift in policing’

Georgia Public Broadcasting (GPB), June 8, 2022, by Riley Bunch: SAVANNAH, Georgia — Sometimes when Savannah Police Department officers are called to a scene of a crisis, those who respond may not look like police at all.

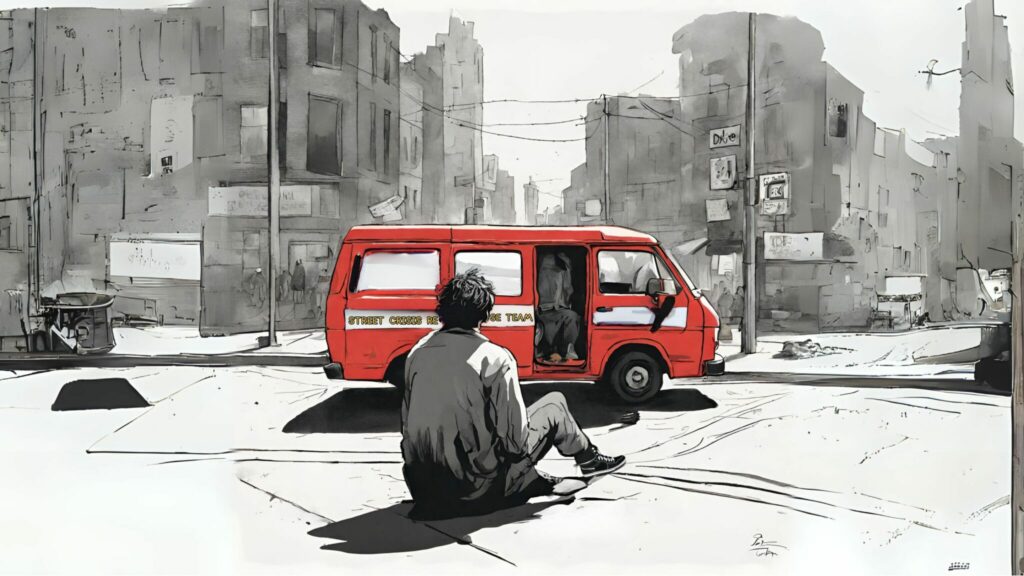

Officers arrive in an unmarked Ford Explorer, donning a simple blue polo and gray khaki pants.

Their SUVs offer more comfort than the usual police police vehicle, with only a thin partition separating the front and back passengers. The seats are soft, not hard molded plastic.

No flashing lights line the top of the vehicles, and the department’s logo isn’t emblazoned on the side.

It’s part of an effort started in 2020 in the coastal city to respond to the growing mental health crisis — a way of de-escalating a tense situation without anyone getting hurt or the person being sent to jail, as was common in the past.

“We have a very subdued look because in Savannah, a lot of people don’t want other people to see them with the police,” said officer Julie Cavanaugh. “So the person doesn’t feel like that they’re going to jail or that they’re encountering a police officer that’s in a full uniform.”

Read more at GPB here.