Overwhelmed with mental health calls, six rural sheriffs make their own plan for better response

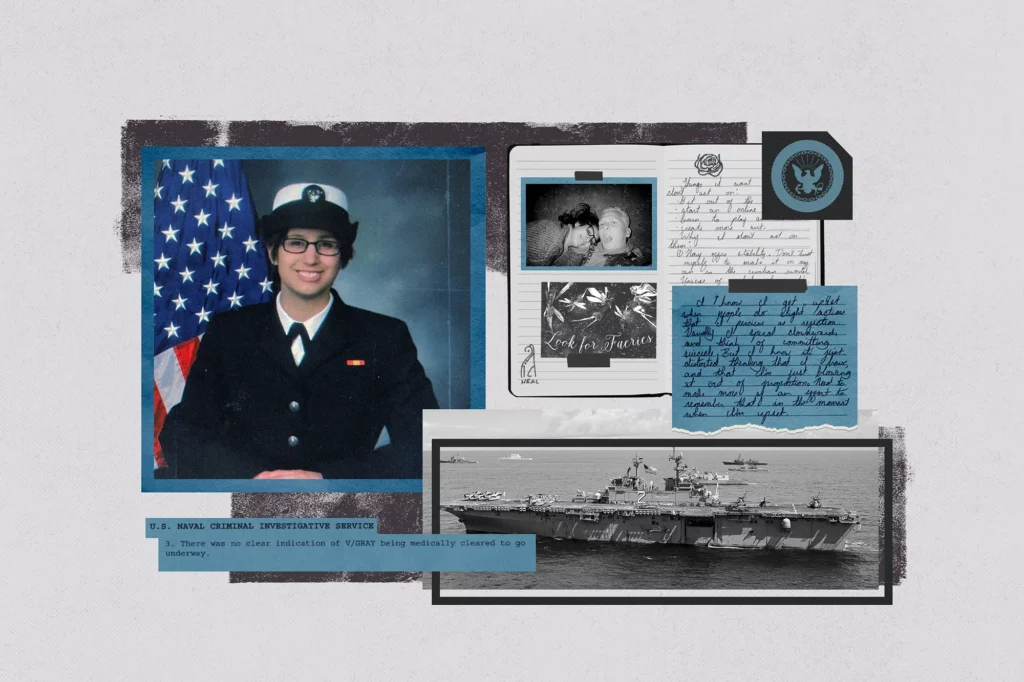

Georgia Public Broadcasting (GPB) by Sofi Gratas, September 13, 2023: Eurie Martin, 58, was walking alone on a rural two lane road in Washington County in 2017, when three deputies from the county sheriff’s office encountered him, responding to a suspicious person call. They didn’t know Martin had a history of mental illness and were not trained to handle people in crisis.

Police footage shows the situation quickly turned hostile. The deputies are seen crowding him, ordering Martin to “get on the ground.” During the interaction, Martin was shocked by stun gun for over a minute and a half. It was enough to stop his heart.

Emergency medical services were called, but Martin died at the scene in police custody. All three deputies who responded to the call on Deepstep Road stood trial in 2021 for felony murder. That case ended in a mistrial when jurors deadlocked, and though it’s been reassigned, dates for a new trial haven’t been set yet.

Washington County Sheriff Joel Cochran said the case was a turning point for his small community in central Georgia.

“That really opened a lot of eyes to realizing that, you know, we have a crisis in general with mental health,” Cochran said. “And law enforcement is just not trained and capable of handling those types of situations.”

When he took office in 2019, Cochran made 40 hours of crisis intervention training mandatory for deputies to help them respond appropriately to people experiencing behavioral health crises.

Yet even with the training, Cochran says his deputies are overwhelmed with calls about mental health crises. His department is not alone.

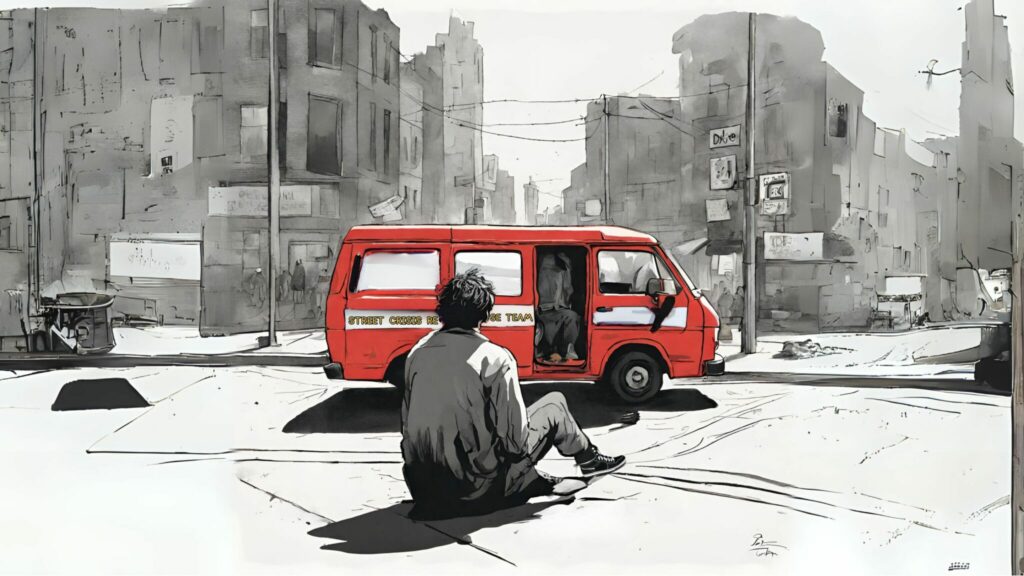

Law enforcement are often the first and only ones who respond to calls when people have a mental health crisis, especially in rural areas where behavioral health providers are lacking or completely unavailable.

Read from Georgia Public Broadcasting here.