The mental health of migrants simmers below the surface as the next looming crisis

WBEZ by Kristen Schorsch, December 14, 2023: Support groups are trying to address the obstacles to care, including language barriers and a persistent shortage of mental health workers.

Jorge Rubiano is a haunted man.

For months, he has tried to find work. For months, he has slept in a shelter, worrying about his wife and mother he left behind in Colombia. Are they safe? Did I make the right decision?

He is haunted by his journey to Chicago, a trip of more than 2,000 miles, during which he says he was kidnapped for a month, then escaped.

He left his country because he says the government threatened his life. There were nights when all he could do was cry in anger. He recalls a phone call with his wife in Colombia, cut short when the bus she was riding on was being robbed.

“Estoy entre dos peligrosos. Si vuelvo es muy posible me matan, y si me quedo no se que puede pasar aquí.”

“I’m still in between two dangers. If I return it’s very possible they kill me, and if I stay I don’t know what can happen here.”

More than 25,000 migrants and asylum seekers have arrived mostly from South and Central America since late August of last year. They are fleeing the collapse of their economies, the lack of jobs and food, and as one social worker puts it, “misery.” Many came here on a bus from Texas, where Republican Gov. Greg Abbott said Chicago and other sanctuary cities that embrace immigrants would provide much-needed relief “to our small, overrun border towns.” The buses haven’t stopped since.

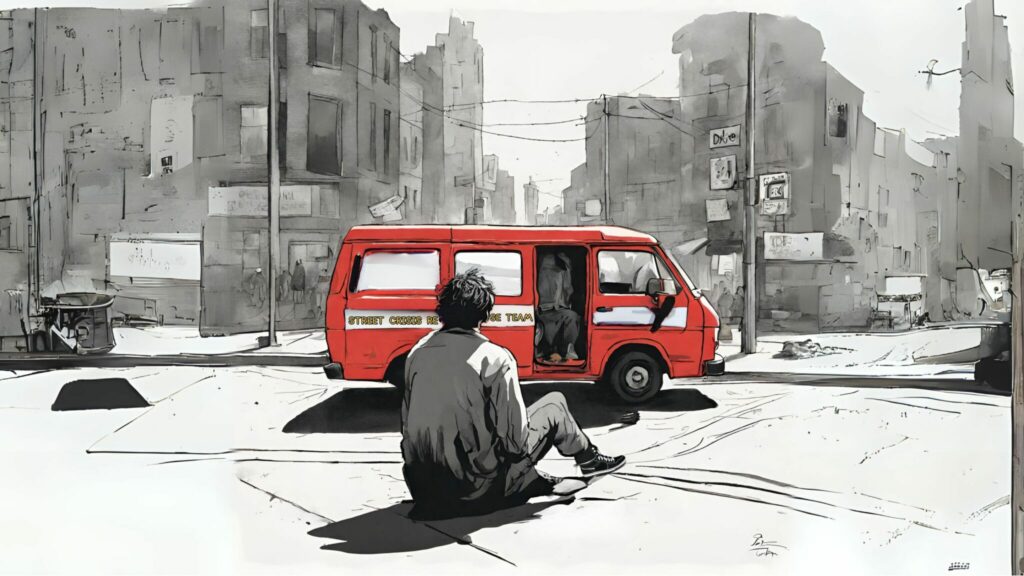

WBEZ interviewed more than 30 people to understand the emotional toll migrants face, the army of helpers who are filling in the gaps of a frayed mental health system, and what’s at stake. Some of those helpers’ efforts are catching the attention of leaders in other big cities where migrants are heading.

For many, the journey here was harrowing. A young girl who fell into a river as her pregnant mother struggled to hold on to her small hand so the current wouldn’t whisk her away. Women who paid to move on from country to country not just in cash, but with their bodies. People who walked over the dead in the jungle and are wracked with guilt over the sick and injured left behind. Families separated once they got to the U.S. border, not knowing when they would see each other again.

Their stories have unfolded across Chicago in the quiet space of a therapist’s office, at a healing circle in the back of a storefront, with a nurse at a folding table propped up outside a police station so relatives inside couldn’t hear.

Read more from WBEZ here.