These Oklahomans Needed Mental Health Care. Instead, They Died in Jail.

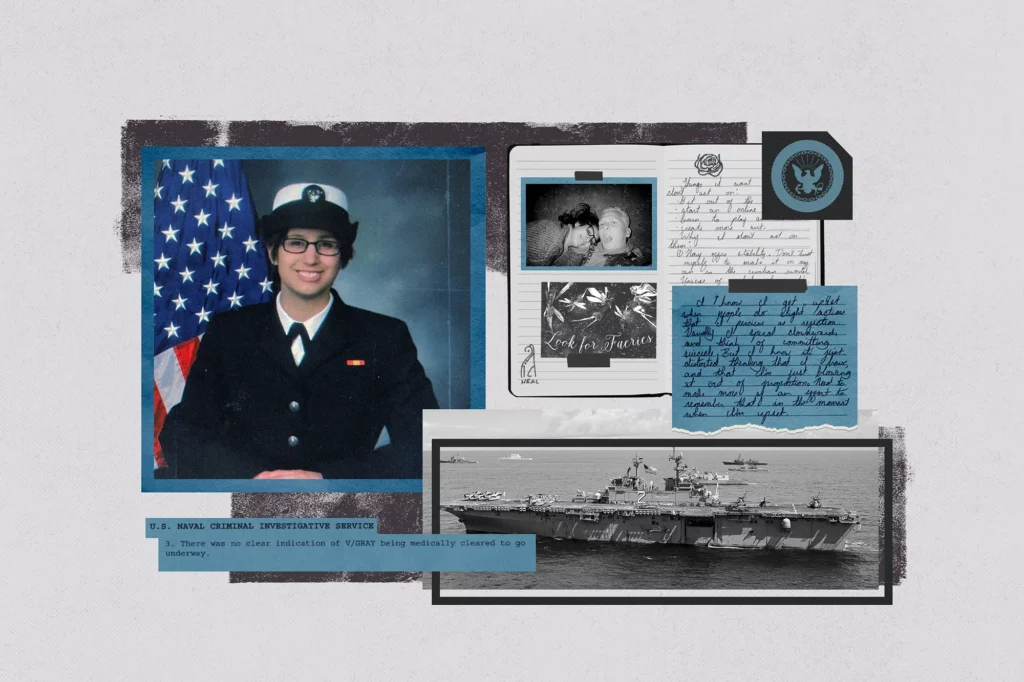

Oklahoma Watch by Whitney Bryen, December 15, 2023: Lena Corona was sitting on the porch of her Seminole home, blood dripping from her hand, when police arrived at 2:45 a.m. Her dad stood behind her, pressing a T-shirt over the wound on his chest where Corona had plunged a shard of glass.

When he called 911 on July 10, Freddy Corona hoped police would take his teenage daughter to the hospital as they had done fewer than 24 hours earlier when she threatened him with a metal rod while in psychosis. But over her dad’s objections, the police arrested the 18-year-old for assault and battery with a deadly weapon.

At St. Anthony Hospital, officers sought medical care for the cut on Lena Corona’s hand. Corona told emergency room nurses that she was defending herself from dark spirits, according to Cpl. Melissa Sharp’s incident report. After medical staff cleared Corona, Sharp drove her to the Seminole County jail where she was admitted while still in psychosis, a symptom of her diagnosed mental illness.

Hours after Corona was booked into jail, her sister called and told a jailer that Corona had been prescribed medication for her bipolar 1 disorder the last time she was hospitalized but had stopped taking it triggering psychosis. She asked the jailer to make sure her sister received treatment. She responded by telling her Corona’s bail was $7,500, money the family didn’t have.

Across the state and country, families like the Coronas can’t access sufficient health care for their loved ones and turn to police for help in a crisis. With law enforcement involved, emergency situations can escalate quickly, leading to arrests and incarceration in jails where detention officers with minimal training are responsible for the health and safety of detainees, which can have fatal consequences.

“I thought a couple of days in there would be OK,” Freddy Corona said. “At least she’d be safe in there for a few days until we could figure everything out. Instead, she just got worse and worse and no one did anything to help her.”

Five days into her jail stay, on July 15, Lena Corona hanged herself in a cell.

State laws guiding mental health and addiction care in jails are vague, leaving it up to jail officials to decide how often to check on sick or suicidal detainees, or when to seek emergency treatment. Behind bars, presumed-innocent people with mental health conditions often face neglect, abuse, or even death.

Last year, 28 jail detainees died from untreated mental health or substance use conditions, accounting for more than half of the state’s 53 jail deaths, an Oklahoma Watch investigation found.

Read more from Oklahoma Watch here.