A community approach to preventing police violence against Liberians in mental health crises

By Tsion Horra

Program Assistant, The Carter Center Mental Health Program

The response to anti-Black violence in the United States and mass deaths from the Covid-19 pandemic globally have demonstrated how profoundly social and public emergencies affect the mental health of various populations.

And trauma in the aftermath of violent interactions with police are carried by those who survive, witness and fear these acts of brutality.

In 2020, we saw protests over police brutality and extrajudicial killings — from here in the United States to the End SARS movement in Nigeria — and a wider awareness that police violence is a public health issue.

As the demand for psychosocial support grows, holistic community-based responses and services become increasingly important.

“A system of care builds on the strengths of the individual and family, and on the strengths of the community where police live and operate,” said Samhita Kumar, associate director of The Carter Center’s Global Behavioral Health Program.

For the past 11 years, The Carter Center’s Mental Health Program has worked in Liberia with clinicians, law enforcement, journalists, primary school teachers and communities to integrate mental health care and anti-stigma training into the country’s public health, education and law enforcement institutions.

Due to a lack of access to adequate mental health care or a lack of awareness regarding mental health conditions, police are often the first called when someone is experiencing a mental health crisis.

With many police lacking in anti-stigma and de-escalation training and armed, these calls for help have instead ended in further harm or the killing of the person experiencing a crisis.

To reduce the likelihood of police violence and to improve the interaction between police and community members who live with mental health disorders, Crisis Intervention Team training was developed in Memphis, Tennessee in 1988 and has since spread around the world.

“This training really helps create connections between law enforcement, mental health providers, hospitals and people living with mental illnesses and their families,” Kumar said. “It’s a collaborative community partnership.”

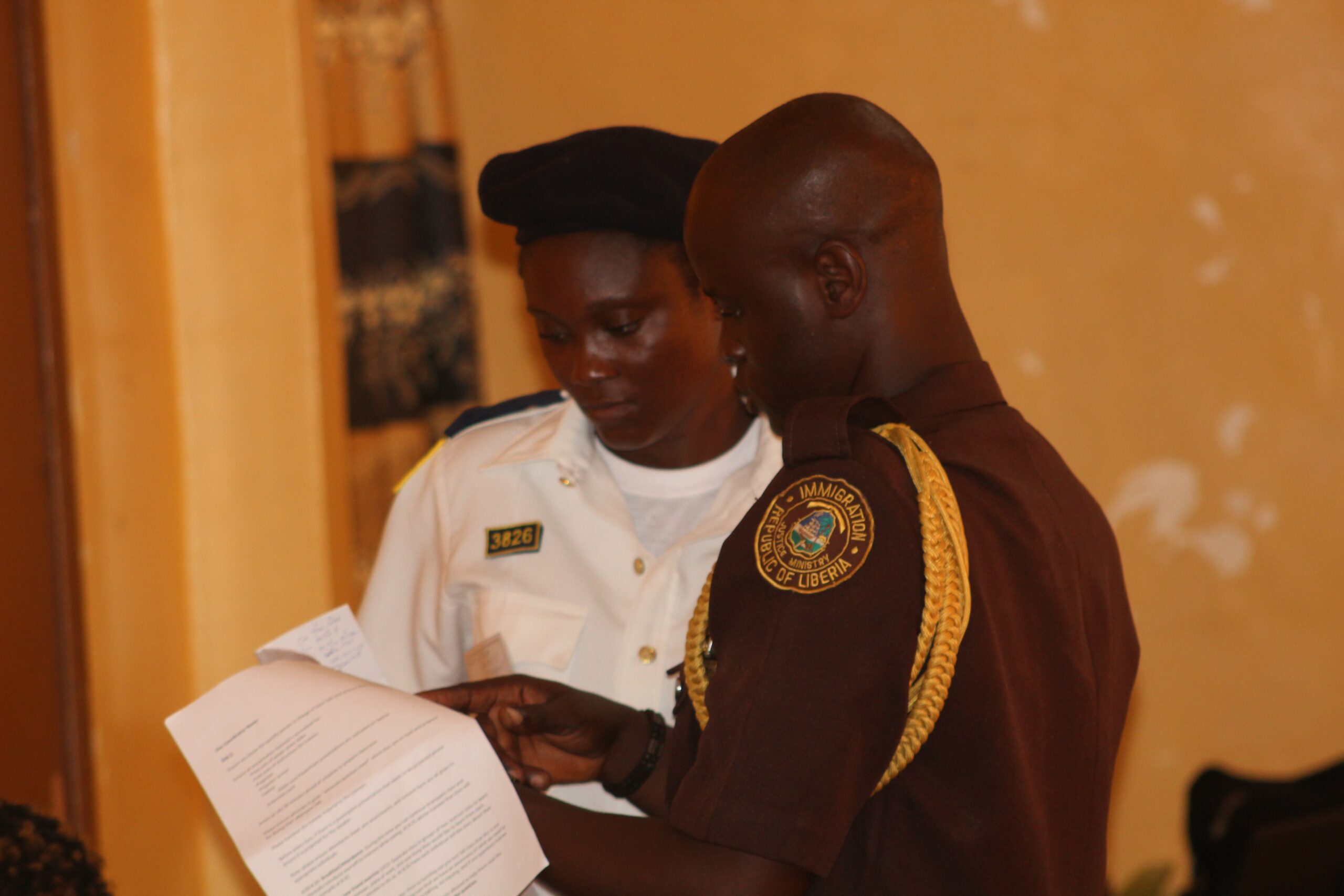

In 2013, the Carter Center Mental Health Program began a partnership with the Liberia National Police to train law enforcement on the Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) model.

Since Crisis Intervention Training began in Liberia, 117 law enforcement officers, including instructors, have been trained in the Crisis Intervention Team program.

Working collaboratively with researchers and practitioners funded by National Institute of Health and CIT International, Liberia became the first low-income country in to implement the CIT model.

As part of The Carter Center’s work to strengthen the mental health care system and the human rights and inclusion of people with lived mental health experience in Liberia, the Mental Health Program has included mental health clinicians and people with lived mental health experience in the trainings to educate and facilitate an enhanced understanding of mental health conditions and referral.

These efforts not only educate law enforcement and mental health clinicians on de-escalation, but also build alliances between the law enforcement and mental health communities to improve community response to mental health crises.

Since the initiative started, 117 law enforcement officers, including instructors, have been trained in the Crisis Intervention Team program.

For long-term sustainability, the Mental Health Program in Liberia is working to integrate the course into the cadet training program at the Liberia National Police Training Academy (LNPTA). A training of trainers (TOT) was carried out in November 2019 for 23 instructors at the LNPTA to facilitate the cadet training program.