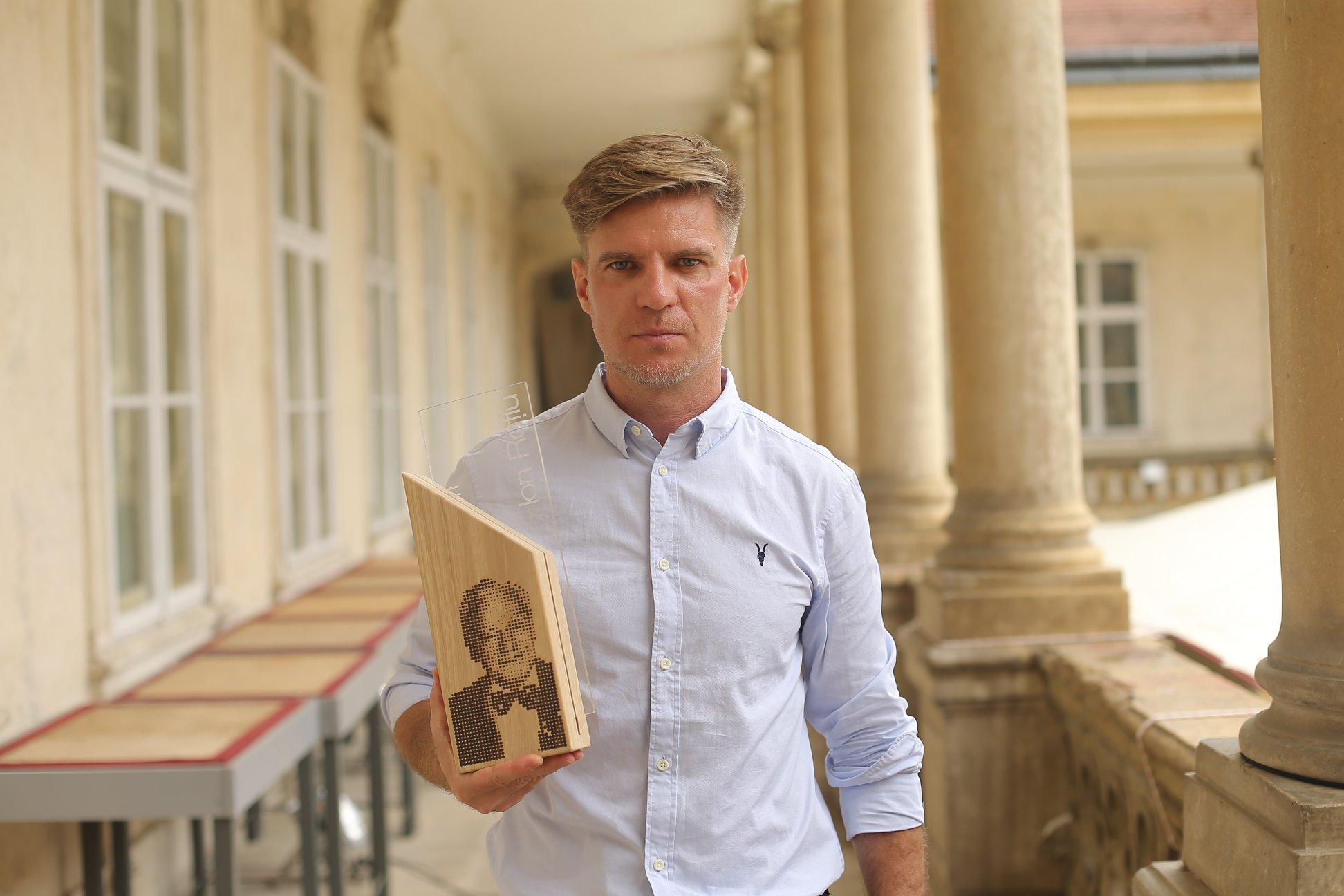

Carter Fellow Paul Radu wins $1.5M Million Skoll Foundation Award

By Susan Pearson Hunsinger

Program Associate, The Carter Center Mental Health Program

Romanian journalist Paul Radu has won many prestigious awards in his career.

A 2007-2008 Rosalynn Carter Fellow for Mental Health Journalism, Radu won a 2017 Pulitzer Prize for his work on the Panama Papers, the Daniel Pearl Award, the Global Shining Light Award and the Sigma Data Journalism Award for covering money laundering.

In April, Radu added the 2020 Skoll Foundation Award for Social Entrepreneurship to the list.

The Skoll Foundation, a private foundation in Palo Alto, California, invests in innovators focused on solving the world’s social problems and awards social entrepreneurs whose work has had significant impact on those issues.

Each awardee receives $1.5 million to scale their work and increase impact over three years, according to the foundation’s website.

The award comes at a pivotal time. Organized crime is growing.

By some estimates, organized crime and corruption, including drug trafficking, the trafficking of women and children and money laundering, account for 20% of the world’s economy.

The Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project that Radu co-founded with Drew Sullivan is credited with reinventing investigative journalism for the 21st century as a public good, the Skoll Foundation noted.

With OCCRP, Radu and Sullivan pioneered an innovative cross-border approach to investigative reporting, combining science and data with traditional reporting.

They created Aleph, a sophisticated set of tools and data software that allows journalists to search and cross reference billions of records to expose illegal activity.

And it’s working.

Their reporting project’s network connects hundreds of journalists and nearly 50 independent member centers across 39 countries.

They have published more than 100 investigations a year, making it one of the largest producers of investigative reporting in the world.

Since 2008, OCCRP stories exposing corruption have contributed to $6.5 billion in fines levied, 308 official investigations, 442 indictments, arrests, or sentences, and 52 high-level resignations or firings.

We caught up with Paul Radu last month to talk about his work.

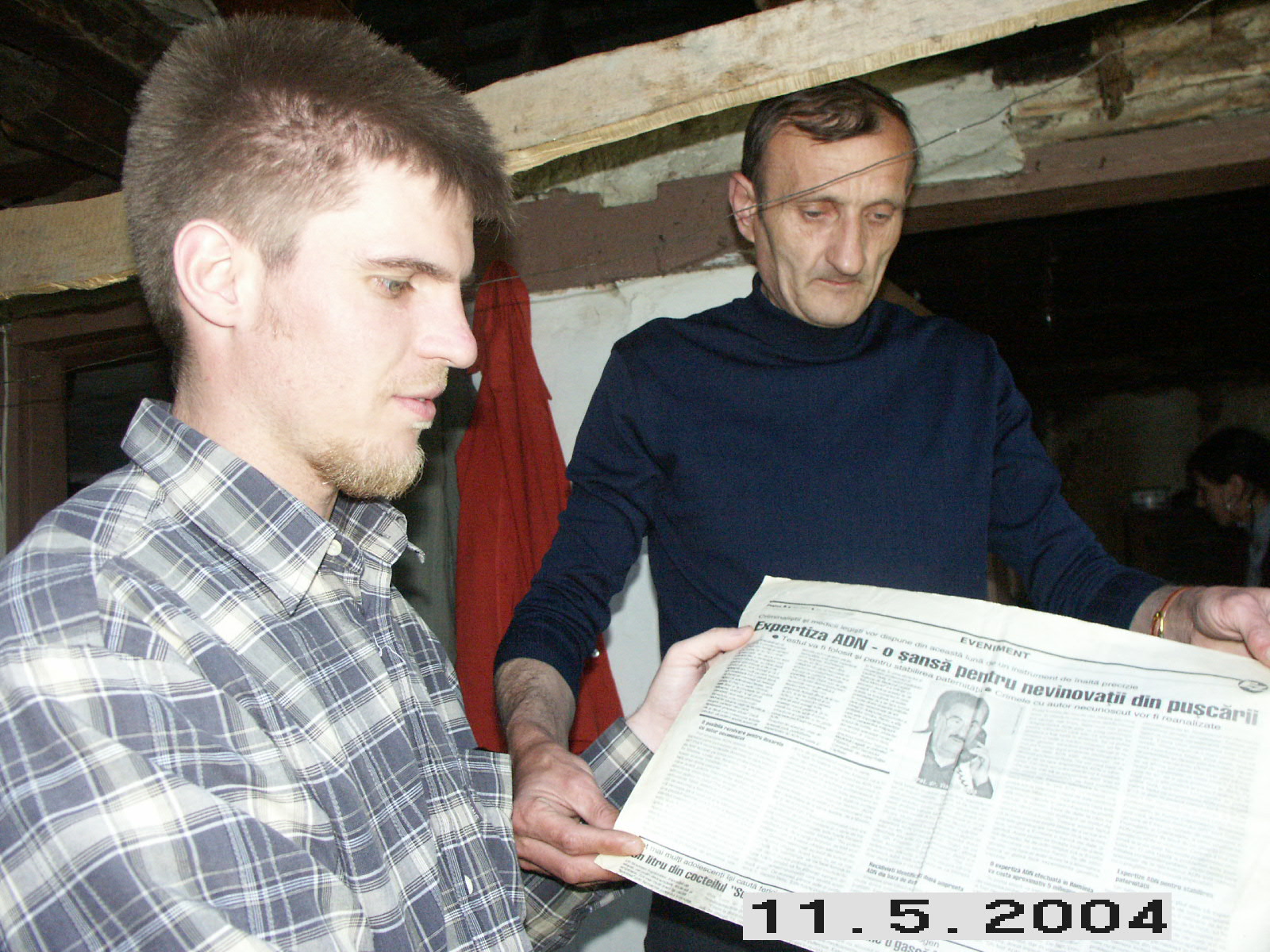

Journalist Paul Radu (left) with Marcel Tundrea, the first person in Romania released from jail after DNA testing proved Tundrea was innocent of the double homicide for which he served 12 years. Here Tundrea shows Radu the article Radu wrote that prompted Tundrea to ask authorities to apply DNA testing in his case. (Photo courtesy Paul Radu).

You pioneered new approaches to cross-border investigative reporting, including your manual “Follow the Money: A Digital Guide to Tracing Corruption.” Why do you believe “it takes a network to fight a network”?

Crime and corruption are like commodities in that they can be imported and exported.

When we started investigating crime, we were doing it one country at a time. We would see the same thing over and over again: Criminals would be forced to shut down in one location and then simply move to another country and restart their same lucrative practices.

Organized crime takes tremendous advantage of networks. We decided to organize our own global network and take a different approach, focusing on cross border activities.

Public data isn’t always easily accessible or cheap, yet it’s the heart of investigative reporting. How is OCCRP changing what’s accessible to journalists?

Our investigative dashboard allows journalists to search for patterns over multiple databases. Our research team can also assist journalists in how to do this. Journalists can then harness the power of multiple data sets and combine that with what they’re seeing in the physical world.

The local content is always crucial. Data isn’t always available online, maybe 60% of it is offline. We’re refreshing our data all the time, but there’s still more progress needed.

We can also provide our journalists with starting points and topics. For example, did Company X really build the railroad or bridge with the public money it received?

Who is included in your network other than journalists?

Civic hackers, global anti-corruption activists, and researchers. We cooperated with librarians from the American Library Association and they are some of the most amazing researchers ever!

How is COVID-19 impacting your work?

“In a pandemic and in times when people are in great need, organized crime will speculate.” – Paul Radu

We’ve assembled a team and an editor in charge of COVID issues. A recent article on our website is “The Convict and Coronavirus: Romania’s Million-Mask Mess” by Ana Poenariu.

It chronicles the defective masks sold to Romania for approximately 800,000 euros by a middleman company controlled by a convicted organized crime associate in a no-bid process. In a pandemic and in times when people are in great need, organized crime will speculate.

You were one of the first two Rosalynn Carter Fellows for Mental Health Journalism in 2007 in Romania and for your project you trained journalists on mental health issues. What changes in the mental health landscape have you seen in Romania since 2007?

Probably the biggest change is that we are recognizing we are at risk as journalists. And that we need to ask for help.

Fifteen years ago, this wasn’t an open discussion. It is now among journalists, although there is still stigma in broader Romania.

I’m proud that OCCRP contracts with an outside service of professional mental health providers and our journalists are able to access these services confidentially.

When you were reporting on human trafficking in the Balkans in the early 2000s, did you have any special mental health training?

When I was undercover, buying women and then taking them to the shelter, a talented psychologist, Iana Matei, counseled them and me.

She taught me how to ask questions and behave with victims in this traumatic situation. I still draw on that.

Do you ever fear for other journalists’ or your own safety?

Of course, it’s always a very serious concern, but having a network is valuable in and of itself. Because the data is shared among so many, it diffuses the situation somewhat.

We also train our journalists in cyber security and our editors in physical security. It’s important to be proactive.

Is there an instance that stands out of someone whose changed as a result of your reporting?

I interviewed Marcel Tundrea, the first person in Romania who was released from jail after DNA testing proved he was innocent of the double homicide he had served 12 years for.

He showed me a clipping of a piece I’d written years earlier, a simple press article covering DNA testing when it first came out.

That article convinced him that he had to ask authorities to apply DNA testing to the evidence gathered in his case. This wasn’t deep investigative reporting. It’s not always about fancy tools, but rather what you can do to help people.

The Rosalynn Carter Fellowships for Mental Health Journalism were established in Romania in 2007. For more information about future opportunities in Romania, please contact Cristina Lupu, executive director at the Center for Independent Journalism.