KQED’s April Dembosky talks about her gut-wrenching investigation into women with postpartum psychosis who kill their children.

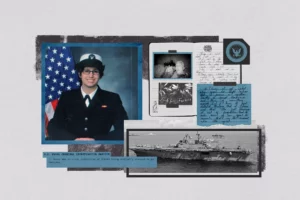

2019-2020 Rosalynn Carter Mental Health Journalism Fellow April Dembosky takes us behind-the-scenes and into her investigation on postpartum psychosis. Her story aired on KQED on February 6, 2020. Read and listen here. It also ran in Mother Jones and the Mother Jones podcast.

By Kari Cobham

Senior Associate Director

Postpartum psychosis isn’t as well-known as postpartum depression in parents. Why did you decide to write about it as your fellowship project?

I had done two previous radio documentaries, one about postpartum psychosis and the other about the insanity defense, and I wanted to do this project to explore how these two subjects overlap.

I produced a radio documentary in 2018 about postpartum psychosis, which focused on ways the health care system was ill-equipped to care for women with postpartum psychosis. Even in the medical community, it’s not well understood, and because of the waxing and waning nature of the symptoms, doctors often miss it. That’s when suicide or infanticide can happen.

I wanted to do this story to explore how the legal system also misunderstands this condition and raise questions about how our courts take such a punitive stance toward people with mental illness.

Carol Coronado, whose case I examined in the story, pursued an insanity defense. This was also something I wanted to explore more deeply after a personal experience I had. Someone very close to me was accused of a serious crime and I was asked to talk to the forensic psychiatrist in that case to support his insanity defense. That’s where I became aware of the ways the science of mental illness does not line up with the law.

Two moms killed their children. Both had postpartum psychosis. One went to prison and one went home.

Thanks to @CarterCenter, @BLNYCNY and @HankKlibanoff for your help with this @KQEDnews story.https://t.co/ZDaUcQ5fGg

— April Dembosky (@adembosky) February 12, 2020

You interviewed and wrote about Carol Coronado, who killed her three young children while she experienced what experts say was postpartum psychosis. What was it like sitting with Carol and her husband Rudy and talking about such an intimate and tragic event in their lives?

The interview with Rudy was one of the hardest I’ve ever done. I have talked to a lot of people about painful moments in their lives, but by the time I arrive, people have processed what happened to a certain extent. Rudy had done a lot of that – he learned a lot about postpartum mental illness since this tragedy and has really made it his mission to speak out about it, specifically to help other dads know what to look out for. He does this by sharing his story, and even after so many times, the feelings are still so raw and present for him. I had to check on him in the days after our interview to make sure he was doing okay.

Carol was the opposite. She says she has no memory of what happened and that the reality of what she did only began sinking in in the years after. So she is incredibly detached, like she has no feeling at all, like it’s something that happened to someone else. It’s clear she’s protecting herself from thinking about it and that she hasn’t had much opportunity to grieve in prison.

But I know this has been hard for Rudy, to not be able to grieve with Carol about the girls, and I realized Rudy’s feelings are still so intense because he’s carrying the weight of what happened for both of them, both he and Carol.

How did you take care of your own mental health as you dug into this story?

In the beginning, I tried to take a lot of breaks. After an intense interview, like the one with Rudy, I tried to give myself down time to process what I’d heard rather than rushing onto the next thing. I would also take a few days to work on another story, so I wouldn’t dwell on it too much.

At a certain point, I had to shift my mind to a place where I could work through all the complex, twisting legal and ethical questions of this story. That protected me somewhat, but it was also quite the shift once I was able to get back to a more emotionally balanced place.

[Related: How journalists can take care of themselves while covering trauma]

You mentioned in your story that California’s prison system doesn’t track how many women are in prison for killing their children. Can you walk us through how you were able to get and analyze the data to add context to your story?

I started by reading through reports and statistics that are already publicly available from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation to understand what kind of data they keep. They have stats on how many women are incarcerated for murder and manslaughter, but they do not keep track of whether the victim was a woman’s husband, co-worker, cab driver, or child.

I filed a Public Records Act request for the names of all the women currently in prison in California for murder or manslaughter, and the county where they were committed. Because no one had requested this before, I had to wait five months for the department to pull the data. I got 1,210 names back, then recruited one of our interns to help me look up every name to determine who each woman had killed.

We did this with various Google and Nexis-Lexis searches to find news reports or court documents to determine which women had killed their kids, how old the child was, and what sentence the woman received. (This also required taking a lot of breaks!)

What’s the moment you still carry with you?

Carol and I had been in touch for about six months when the holidays approached. Carol sent me a Christmas card in the mail with an illustration of a kitten and a puppy, each tucked into a Christmas stocking. The message on the front said “All is Calm.” She signed the card, “Carol s.y.x.” (The letters are the first initials of her children’s first names.) Everything about this gesture floored me.

What’s one thing you want readers or listeners to take away from your story?

At its heart, this is a story about justice. In the United States, we already make a distinction between different types of killings. A man who shoots the cashier at a 7-Eleven during a robbery is different from an elderly person who gets the sun in their eyes while driving and hits a motorcyclist by accident.

Two dozen other countries determined that a woman who kills her kids because of postpartum psychosis is much closer to the latter scenario than the former.

When we lock these women up for the rest of their lives, we are tacitly absolving the systems that failed her. We are ignoring the patterns and risk factors that led to these tragedies and, in turn, we are missing the opportunities we have to prevent them.

April Dembosky is a 2019-2020 Rosalynn Carter Fellow for Mental Health Journalism and the health correspondent at KQED Public Radio in San Francisco where she covers health policy and public health and has reported extensively on mental health and end-of-life issues. Learn more about April.

Fellowship applications are now open until April 29, 2020. CLICK HERE TO APPLY.

Got questions? Review our FAQs here, too.